Looking back there are definitely only a handful of times that I’ve been nervous about camping: There was the first time I ventured into the Arctic all the way back in 2001 when I was eighteen, then there was my little solo expedition climbing a 5700m mountain in the Peruvian Andes in 2006 (which was also the first time I’d been that high or climbed a high altitude mountain). This was quickly followed by my solo attempt on Aconcagua a couple of months later which is a little short of 7000m. In 2008 when my colleague and I made our first attempt at a spring crossing of the remote Penny ice cap on Baffin Island (it was really cold and my feet froze) and finally our return trip in 2011 (for which I was nervous about my feet freezing again). I make that five times with the last one a full decade ago. Last week I added to that count.

CREATING A FERAL CHILD - PART 1

Just like every other parent in history our world was turned upside down, inside out and the wrong way round. There is a space where adventure can exist whilst safeguarding the most important part of your being. We didn’t really have a choice: Stronger than the yearning of adventure is the desire to raise our baby with our values, to let him experience what we cherish most in the world and the only way to do that is letting him grow up (semi-) wild.

Way up on Table Mountain

The cable cars silently glide over my burnt orange rocky perch and from this vantage point I can peer into the glass fronted levitated car. Inside is a cram of people all sporting sunglasses sunhats and DSLR cameras slung around their necks. I felt smug for my route up table mountain, the solitude I had coupled with views overlooking the cape peninsula surely beat being penned in a cable car. If anyone in the car looked downwards they may have seen me waving and I'm sure they would've felt the opposite, feeling smug for their quick and comfortable journey up to the top. But for any mountain it's about the journey more than the destination which holds for even for this benign looking mountain and hiking/scrambling up was the only way I would be getting to the top.

Interview: Meet The Accidental Adventurer

Interview I did for Wolsey. Check it out on https://www.wolsey.com/blogs/magazine/meet-the-accidental-adventurer

Most explorers grow up dreaming of adventures in the frozen wastes, inspired by titans like Ernest Shackleton, but Vijay Shah stumbled into his life of adventure

Vijay Shah was part of the first British ski team to cross the Arctic’s remote Penny Ice Cap on Canada’s Baffin Island, opening up a new route in the process. This achievement was added to his experiences of solo-ascents in the high mountains, and guiding groups in the Peruvian Andes as a British Exploring Society Leader.

This life on the edge is a far cry from a seven-year old Vijay’s predictions for his future. Growing up in the urban landscape of East London he wrote in primary school that he wanted to grow up to be an accountant. The outdoors was a closed book as he grew older until a British Exploring Society expedition to Svalbard in the Arctic opened his eyes, and within five short years he was leading his own expeditions...

Q: Tell us about your Penny Ice Cap expedition?

A: ‘Our crossing of the Penny Ice Cap was the epitome of what an expedition should be. Start of with some heavy emotional baggage of having had to unceremoniously retreat off the same route three years earlier due to frostbite. Mix it up with rescuing a lost polar bear cub and bringing it back to its mother. Then finally throw in the danger of skiing over very thin sea ice all to the backdrop of some of the most amazing vistas on the planet, and you’re left with a picture perfect postcard of an adventure!’

Q: Did you think you’d become an explorer when you were growing up?

A: ‘If you were to tell a younger me that I could one day call myself an ‘explorer’ I’d say you were mad. Explorers were something I couldn’t fathom or relate to. They were white for starters, making it hard for a younger me to relate to them. And what made them want to risk life and limb, and have a thoroughly miserable time of it for some ideal or record? That was completely alien to me. In contrast, the ideals that my community upheld were family, education and hard work; activities other than these three were ‘unnecessary’ and ‘frivolous’.’

Q: What did discovering the outdoors do for your mindset and sense of self?

A: ‘I wouldn’t say that I knew that I was missing something in my life before I discovered the outdoors, but after I did it was clear there was something missing before that. Discovering the outdoors felt so natural and real, and far more precious than any of the creature comforts that we’re taught to aspire to.

‘Once I’d pushed past the boundaries of creature comforts, being in the outdoors I felt I was answering some innate yearning that I hadn’t known existed. I have never felt as peaceful or content as when I’m out on expedition or remote travel.’

Q: You’re a qualified aerospace engineer – do you bring that expertise into expeditions?

A: ‘Absolutely. In the Arctic our survival is dependant on our equipment – half way through the Penny Ice Cap expedition we set up camp after a hard day’s skiing to find that our stove didn’t work. Despite having snow and ice all around us, without a working stove we may as well have been in a desert, and as all our food was dehydrated we would have no food either.’

‘We carried a spare stove but that didn’t work either; absolutely bizarre and very unusual for both of our stoves to not work at the same time. A sense of urgency was now setting in. All three of us were inside the tent cleaning and changing parts of the stoves like some sort of factory, but the stoves just wouldn’t light. Meanwhile the temperature was descending rapidly. We were approximately nine days of skiing away from civilisation in any direction, but we could only go on for a maximum of three days without water and food – this was getting serious.’

‘Looking at things systematically and using my engineering knowledge, I realised that the probability of both stoves and all our spare parts not working was miniscule to non-existent – there must be something else. After checking our fuel source there was only one possible reason left: oxygen. Immediately I completely opened all the vents of the tent and finally the stoves roared to life – the sweetest sound I had ever heard!’

Q: What’s the most valuable lesson you’ve learned about leadership in the outdoors?

A: ‘Listen. It’s such a simple thing yet we fail at it so often. It’s easy to think that as a leader we always know best, but a team that feels they have been listened to and heard are much more compliant, and more willing to follow you.’

Q: What’s the best piece of outdoors advice you’ve ever received?

A: ‘It’s not your equipment that will get you through but your attitude. When it gets tough, it doesn’t matter how good your equipment is if you don’t have the heart, the belief and the determination to get through it. But if you do have the heart and the tenacity, then you can achieve the extraordinary.’

Q: What’s been your most nervous moment on an expedition?

A: ‘I was on a short alpine holiday in the French Alps and we were attempting a simple route leading from the top of the Mer de Glace glacier in Chamonix. We started at 2am due to the high temperatures during the day but by 9am the temperature was over 25°C celsius and it was heavily affecting the snow quality, so we decided to retreat.’

‘Suddenly my partner slipped in the snow and fell – the rope between us stopped him, but it pulled me off my feet. I dug my axe into the snow but it didn’t bite at all and I hurtled pass my partner. There was an open crevasse below and I fell into it – the crevasse narrowed as it descended and after bouncing off the ice walls I became wedged horizontally between them, facing downwards. All I could see was the blackness of the crevasse below. I couldn’t move my arms, and my legs were freely dangling. We were forced to call for a helicopter rescue, which was the longest wait of my life.’

Q: And your most rewarding one?

A: ‘When I summited Nevado Pisco at 5,752m I was all alone on the summit. The views were spectacular, and especially amazing as I had solo climbed the mountain, my first alpine style ascent. There was not a soul to be seen, or heard, or who knew I was up there. There is a certain gravitas that you cannot experience anywhere else other than when your fate is solely in your hands.’

Senja, Arctic Norway - Cheap Accessible Adventure

Scandinavia is so accessible to us in the UK with and with the ‘last wilderness’ in Europe it really is a must for anyone loving the outdoors. Arctic Norway is even more accessible than most of Scandinavia through the gateway town with international airport Tromso. I’ve flown through Tromso before, heading over to the high Arctic islands of Svalbard but on this occasion I was keen to see what was there to do with only one or two weeks to spare.

That’s where we discovered the island of Senja and spent six days traversing the island, hardly seeing a soul. So if you’re competent in wild camping, love hiking and can read maps in low vis. (and like that sort of thing) then this is really awesome trip. Plus, it’s a super cheap trip if you play it right.

From Tromso, you can take a ferry, that takes only a couple of hours, that drops you to the tiny little crossroads of Silsands and from there you’re on your own. Heading straight up into the hills of the interior you have the entire island to yourself.

Water can be scarce in the high interior where there aren’t many rivers and if you’re lucky enough to have fabulous weather, like we did, then that means that the small streams that exist will be very low. So make sure you have plenty of water containers to fill up when you do find a water source and enough fuel to boil away water taken from less than perfect sources.

Hiking across the interior takes you over a mountain pass. Despite it only being around 1,000m high, being this far north means that you will have to pass over snow slopes and it can get bitterly cold with the weather exposure even in mid-August.

Despite not seeing another person, we did see plenty of reindeer. Having spent a fair bit of time in Scandinavia I know how common reindeer are and that they don’t really fear humans at all. Many a times I’ve woken up in my tent to the sounds of a herd of reindeer walking straight through our camp. As well as not being scared by humans they are also not bothered or interested in us. But that was different on Senja, clearly not seeing humans that often they were enthralled by our presence and kept on hiding behind the next rise to see us before running off to try and sneak up a different way to get a view. We were completely bemused and we enjoyed turning around every few minutes to find a couple of reindeer following us. They will stop in their tracks, frozen like a children’s game and start again when we turned back around.

Depending how quick you go, you’re looking at 4-8 days to get to the southern side of the island where a ferry leaves fairly frequently. Be sure to check out the days and times and make sure you’re there on time. You cannot bet on the weather but you can bet on the ferry times.

At a push, if you’re well organised, you could do this on a week’s trip, ideal for those of us with limited holiday. We took two weeks out and spent the second week exploring Tromso and other parts of the Arctic.

If this does inspire you to get to Senja send me over a photo. Happy planning!

Adventures in mid-England

We are nature people. We love the hills, mountains and coastline. Having traveled the world and lived across Western Europe I can hand on my heart say that the UK has some incredible coastlines and mountains and we enjoy nothing better to do on our weekends than to experience these wild places. So it was with trepidation that we moved inland to landlocked and flat Oxfordshire, a place so unfamiliar to the things we love that, despite the extensive countryside, we felt cooped in.

That's when we got hold of an inflatable boat. That’s when we discovered the rivers.

ASTRONAUTS: WHY THE FUTURE MUST HAVE WINGS

**SPOILER ALERT** If you haven’t seen it yet, watch Astronauts: Do You Have What It Takes? Episode 4 on iPlayer first.

One of the tests that we were given was to present to the panel on a topic of space exploration. Being an aerospace engineer my talk was on a topic that has fascinated me since childhood: Access into Space.

Why The Future Must Have Wings

The hardest part of space travel in our near solar system is getting into space in the first place; out of our atmosphere.

So far the only way we have reached orbital spaceflight is by rockets and these, on the whole, are inefficient, expensive and unreliable.

In comparison, aircraft are very efficient, reusable and for anyone who has flown half way across the world on holiday, incredibly affordable.

In order to understand the difference between these two technologies that have developed over a similar timeframe we really need to understand how a rocket engine works:

· A rocket engine operates under the same principle of if release a blown up balloon. By accelerating a large amount of gas out of the back, an equal and opposite force is imparted onto the rocket pushing it upwards, as described by Newton’s third law of motion.

· The rocket is generating these hot, compressed gases internally through combustion. For any combustion be it a rocket or a campfire, you need three things: a fuel source, an oxygen source and a heat source. The rocket carries all of these components on board with it in stored energy and as a result becomes extremely heavy. This is evident when we see that the oxidiser is six times heavier than the fuel source!

· But this does give it one big advantage, the rocket can operate in the vacuum of space but must result in expending it’s stages as it goes up to reduce mass. And the atmosphere is just a hindrance.

In comparison, the airliner doesn’t see the atmosphere as a disadvantage but uses it beneficially in three different ways:

1. The atmosphere provides the aerodynamic lift on the wings providing the upwards force opposing gravity.

2. Instead of carrying the oxygen with it, the jet engine uses the oxygen in our atmosphere for combustion, and

3. Crucially the jet engines use the air as the working fluid or propellant. The big fans and compressors, suck the air in, compress it, heat it up in the combustion chamber and accelerate it out the back creating the equal and opposite force pushing the aircraft forward.

A much more elegant and efficient solution. Clearly the future of space access must our atmosphere as a benefit rather than always seeing it as a hindrance.

That’s why there is a lot of interest in developing single-stage-to-orbit spaceplanes.

A spaceplane takes off and lands just like an aircraft and uses an air-breathing engine and wings to climb to the upper reaches of our atmosphere travelling at Mach 5, or five times the speed of sound. As the air becomes too thin for the air-breathing engine, the intakes close off and it switches to a rocket engine, accelerating to Mach 25, for the last and final push into orbit.

Now imagine this, as our single stage to orbit vehicle hasn’t jettisoned it’s fuel tanks on its way to orbit, as soon as we reach orbit we have many more options open to us: We can refuel the spaceplane with a conveniently placed orbital refuelling station giving it enough fuel to gently pop over to the moon for a supply trip or a tourism visit and after a few days it will coast back to Earth and re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere. But the benefits don't just stop there, with the much superior re-entry characteristics the spaceplane offers it can land on one of several runways around the world and after a quick check over, a refuel, it is ready to go again. Completely reusable.

And that is why the future must have wings.

Astronauts: Do You Have What It Takes? Episode 5 is on Sunday 24th September at 8pm BBC2.

ASTRONAUTS: DOCKING ONTO THE INTERNATIONAL SPACE STATION

**SPOILER ALERT** If you haven’t seen it yet, watch Astronauts: Do You Have What It Takes? Episode 3 on iPlayer first.

I remember a time when I was seven or eight and my brother nine or ten years old and we used to walk 400m away to a Scouts friend’s house to play on his computer console. He had a Nintendo Entertainment System and we used to marvel at how he used to navigate the two dimensional terrain of Mario Brothers and save Princess Peach with so much more finesse and speed than we could muster. We begged our parents to buy us one but finances and ideology left us disappointed. So the only times we got to play in these pixelated virtual worlds was at friends’ houses or when we were older, at the local video rental store that had an arcade: In the evenings and especially after the hour of prayer at the local mosque teenage boys crowded around the arcade waiting their turn on Street Fighter II. It was the ultimate fighting game, requiring unbelievable speed and muscle memory to enact the combination of moves required to beat your opponent. All I could do was stand on tiptoes trying to get a view and not be pushed out by the older kids. The few times that I did manage to get to the front and challenge the winner, my 20p was wasted in a matter of seconds.

What’s all of this got to do with the astronaut selection? The answer is that I wish I had played a few more video games and the reason for this will become apparent a little later on.

It’s now episode 3, and the tests are becoming more difficult. I couldn't imagine a more nerve wracking test. A three-time astronaut and former commander of the International Space Station (ISS) sitting next to you, telling you that within ten minutes you have to dock the Soyuz capsule onto the ISS. It was a dream come true and I was in awe of what we were asked to do.

Both the Soyuz and the ISS are pinnacles of human endeavours in space. The ISS is the multi-billion pound product of an incredible collaboration between fifteen countries and has been permanently inhabited since the year 2000. It is the largest space structure ever built and can easily be seen with the naked eye (there is an app for that) zooming across the night sky. It orbits Earth every 90 minutes making the inhabitants of the ISS the fastest humans in the world.

The Russian Soyuz is the most successful human transportation space vehicle ever created and since 2011 when the Space Shuttle retired it is the only crew transportation vehicle to the ISS. Devised in the 1960s and still flying today it has the longest operational history of any spacecraft and the safest. There is a Soyuz spacecraft permanently docked to the ISS at all times, serving as an emergency lift raft and if you see any cosmonauts or astronauts arriving or leaving the ISS it would be via a Soyuz.

Thus, docking a Soyuz onto the ISS is one of the most important training tasks an astronaut must become competent at. Failure to dock would mean that crucial supplies and a changeover of astronauts would not be able to happen. But that is not as bad as crashing into the ISS, as Chris Hadfield had put it, going too fast at docking could cause a rupture of the ISS killing everyone on board. But it doesn’t end just there, if the ISS breaks up upon a crash, a cascading amount of orbital debris travelling at 17,000mph could end up making that orbit completely unpassable.

Hence the deer in the headlights moment.

The German Aerospace Center in Cologne, Germany where the simulator was located is also where the European Astronauts Corp is located (right across the road). Both Chris Hadfield and Tim Peake have trained there, in fact Tim’s name was still on one of the rooms we were using. The simulator was the same as that which the astronauts train on and is a replica of the actual Soyuz spacecraft controls.

To dock successfully not only did we have to manoeuvre the Soyuz to the right spot in all three spatial dimensions but also be travelling at the right speed. Too slow and you’d bounce off, too fast, well, you would crash. It required a good level of spatial awareness, good hand eye coordination, speed and nerve. I was so close to docking, but my crosses were ever so slightly misaligned and so I backed up and the time ran out.

Interestingly, those that did well at this test were either a pilot or gamers. After this test and the Mars rover test I wish I had played more computer games. The right sort of games can help develop your 3D spatial awareness, memory and hand eye coordination. The right sort of game can help with strategy and tactics. Computer games are not just devilish past times that would lead to a lifetime of underachievement as I was brought up to believe but offer valuable skill sets that are becoming increasingly important. We are living in a technological revolution where human-machine interfaces are becoming commonplace and developing those skill sets are becoming important not just for astronauts but for all manner of jobs: Airline pilots can become qualified on a simulator alone, surgeons will soon be controlling small operating machines, drone camera operators are already in high demand.

Astronauts: Do You Have What It Takes? Episode 4 is on Sunday 10th September at 8pm BBC2.

ASTRONAUTS: That Darn Rover!

**SPOILER ALERT** If you haven’t seen it yet, watch Astronauts: Do You Have What It Takes? Episode 2 on iPlayer first.

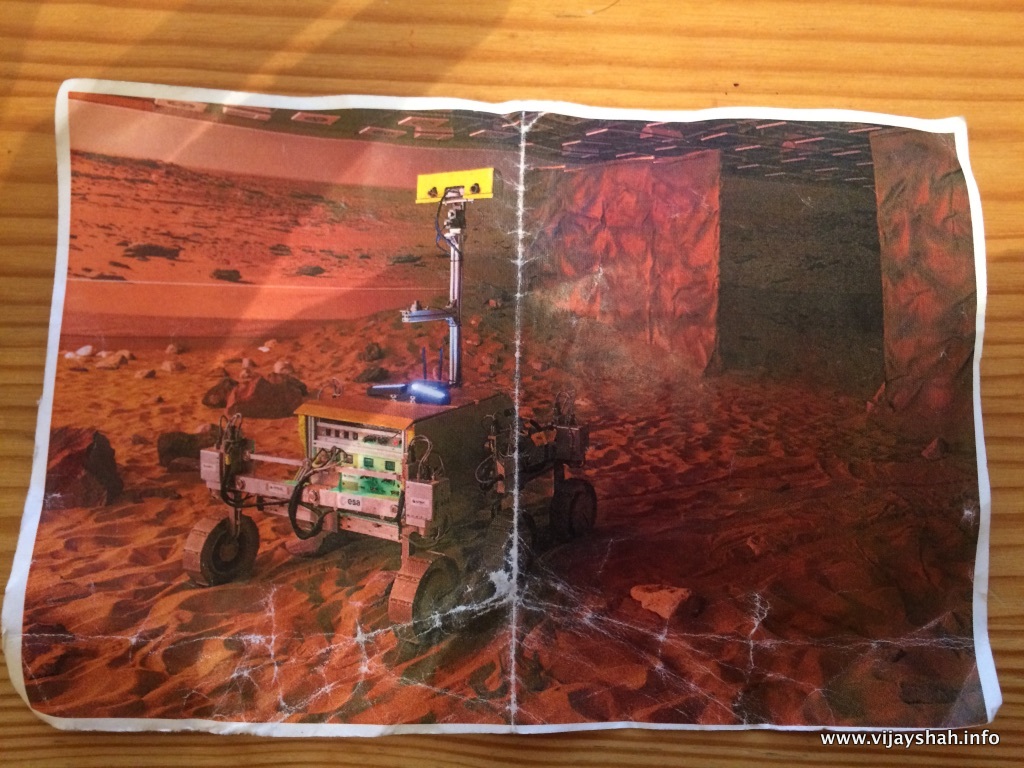

It’s pretty incredible to think that we have had not one but two rovers on Mars, exploring the surface of the planet, sending us back scientific data like never before. Both Spirit and Opportunity arrived on the red planet in 2004 and over a decade later Opportunity is still roving! Controlling the rovers though happens at NASA but the time it takes to send a signal to Mars is an average 13 minutes. So to send a command to the rover and for it to respond to you would take about half an hour which would be a pretty slow conversation.

This was the premise of the test where we had to control the rover ‘Bridget’. The scenario was that at some point in the future we may have a human crew orbiting Mars, just like the International Space Station orbits Earth. In order to find suitable places to land or to explore before sending astronauts down it makes sense to send a rover, Bridget, to determine which places are the best. Like NASA’s Spirit and Opportunity rovers, Bridget is also powered by batteries which are charged by solar panels. Going into a cave is thus incredibly dangerous for a rover because if the batteries deplete whilst still in there the rover is lost forever. On the flip side, caves are incredibly attractive if humans are to visit Mars as they would offer a natural protection against dangerous solar radiation.

By controlling the rover from orbit around Mars instead of from Earth it would be possible to control the rovers in close to real time and that is exactly the training that UK astronaut Tim Peake did in 2016. From the ISS in low earth orbit he controlled Bridget, on Earth, using the same setup as we had. It is amazing to think that this was exactly what astronauts are training for (click here).

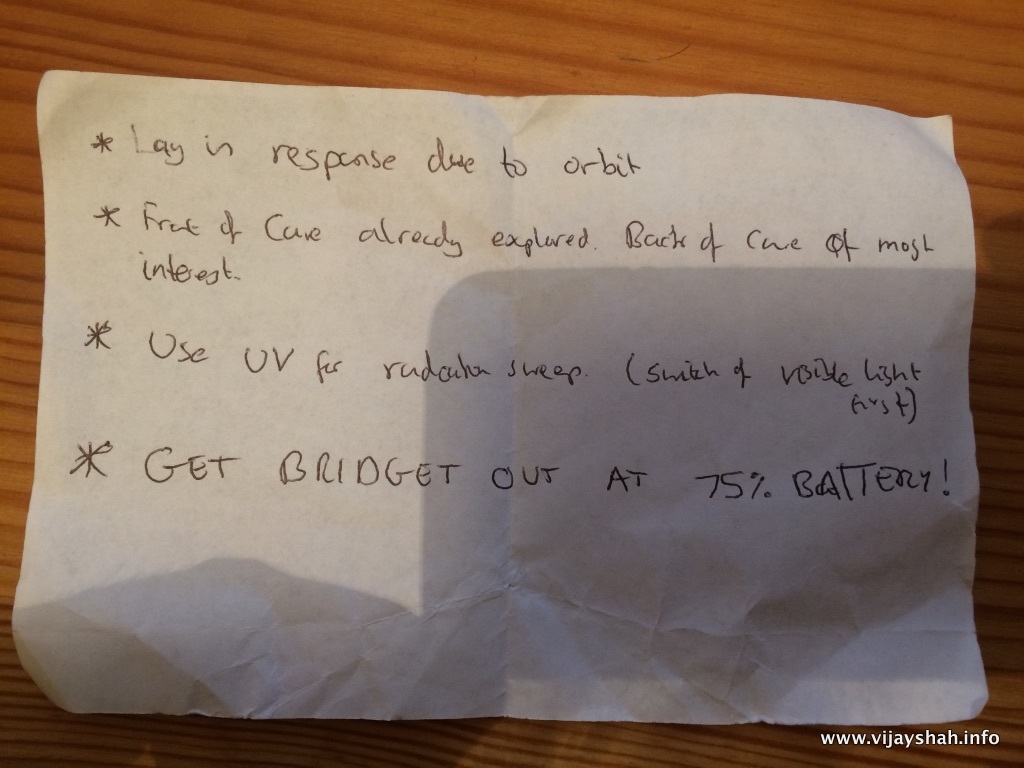

The test was to discover parts of the cave that were of most interest, as it so happened, the most interesting parts of the cave were right at the back, the farthest away from the entrance! But also, just like in orbit, there will be a delay in the signal, making controlling Bridget somewhat difficult. I still have my notes from our initial group briefing.

The last point was the basis of my own tactic. Not knowing how easy it was to control with the lag in the response time and the fact that it was a very slow moving rover, 4cm per minute, I wanted to make sure there was sufficient time to get Bridget out of the cave. As I soon found out, my strategy of finding the targets was poor but by enacting my retreat at 75% battery I overcame a moment when I really thought I would lose the rover, and by doing the slowest three point turn in the solar system I got her out of the cave, just in the nick of time.

Everyone that sent Bridget into the cave had to change their plan to what they discovered, especially as not all of the information we were given was accurate. Those plans that had a lot of manoeuvres suffered the most from dealing with the delayed response. The best plans though used all of Bridget’s tools to the maximum. It turned out that the UV light is actually quite powerful and so you didn’t need to get right to the back of the cave to spot the targets! Both James A and Jackie figured this out quite early on and as a result did extremely well. James A, though, didn’t even have to worry about hitting any obstacles on the way out as he just followed his own tracks back out. Genius!

Episode 3 of ‘Astronauts: Do You Have What It Takes?’ airs BBC 2 at 9pm on Sunday 3rd September.

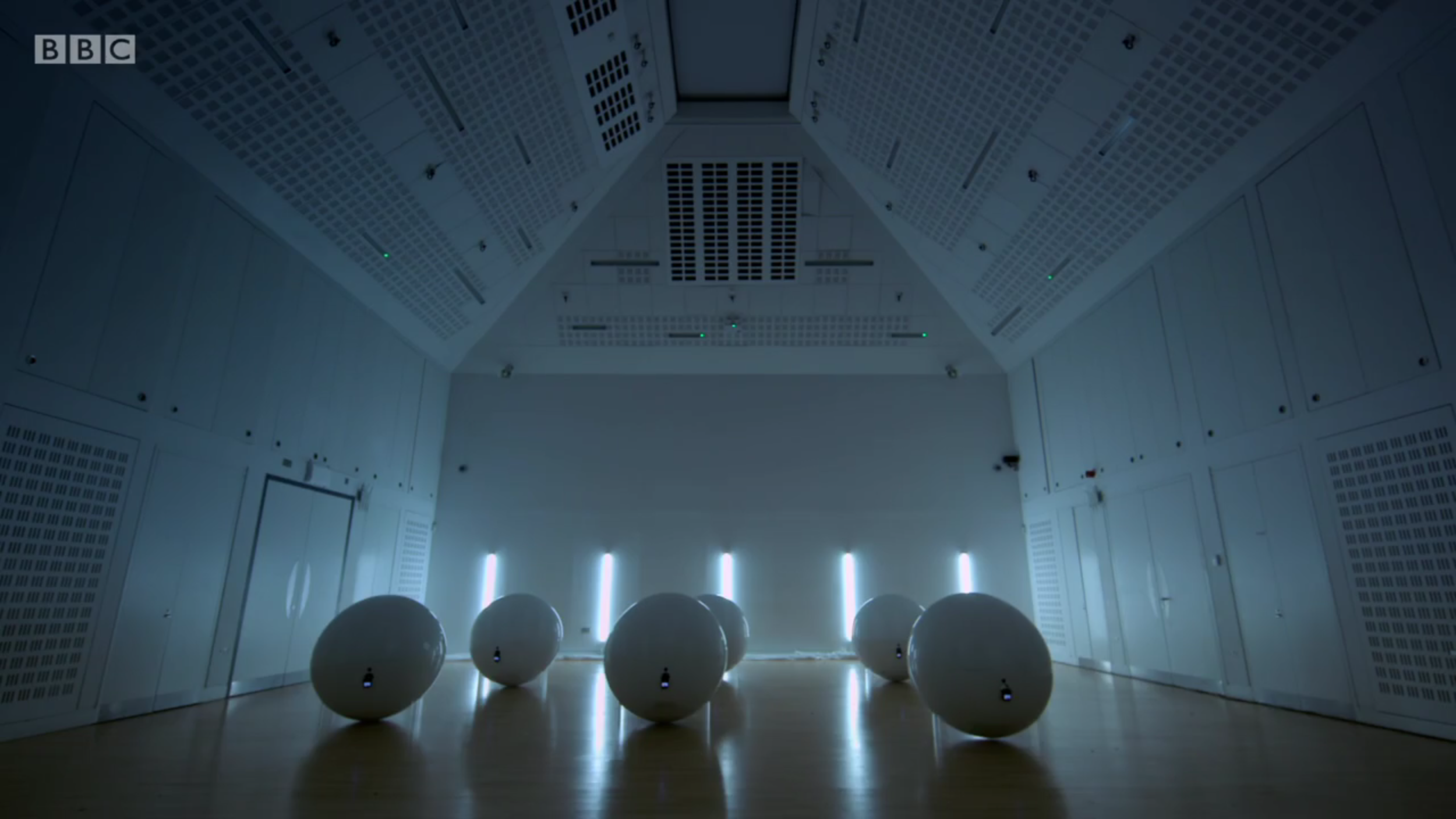

ASTRONAUTS: TESTS and PHOBIAS

As we stepped into the pods and sat down cross-legged we found out for the first time what the task was. A moment later the lids were fitted onto our pods and it went dark. The test started before we even had time to digest what we were supposed to do.

We had no notice of the tests, no preparation time. We had to be on point at all times. We were chaperoned in a minibus, sometimes blindfolded and ushered into a waiting room. There we could be waiting for 10 minutes or seven hours before it was our turn to do the test. But there is no point in feeling hard done by if you had to wait for ages for your turn, it will be mixed up for the next test.... and seriously, does anyone really think that an astronaut gets a proper night's sleep right before launch?

The pod test was a two part test: 1) Lace up our boots in the dark, 2) estimate 20 minutes. What were we being judged on? That was a question that we had plenty of time to think about. The real test though was claustrophobia. As an astronaut you cannot be claustrophobic. You are in small and tight spaces all the time and for long periods of time. It's not just for launch or landing. Even in the vacuum of space, on a space walk, which you might think of as the greatest open space there is, the mask and breathing apparatus can trigger claustrophobia. For anyone that has been SCUBA diving will surely attest to that.

Interestingly, it was a similar size pod design that NASA were considering as one possible emergency evacuation procedure if damage was found on the space shuttle orbiter post the Colombia disaster in 2003. In that tragic accident, damage to the heat-shield sustained to the orbiter at launch led to super heated gases penetrating the vehicle upon re-entry into the Earth's atmosphere and tore the vehicle apart. No one survived. With these crew escape pods, if damage was found on subsequent flights whilst in orbit, a further shuttle would be deployed and the crew could transfer to the undamaged shuttle via these pods. Incidentally the pods were never used and the Space Shuttle was retired in 2011.

Whilst in orbit an astronaut's time is like gold dust and that was the object of the next test. The blood test was an assessment of following a complicated set of procedures where safety and injury is at stake. The reason why an astronaut must be competent at taking their own blood instead of asking a fellow astronaut to help out is because an astronaut's time is the most valuable commodity there is. If two astronauts are kept busy to take blood that is a lot of time wasted. It was also testing for other common fears: The fear of needles or blood. None of the candidates shied away from it though and kudos goes to Merritt for persisting and getting it right with her non-dominant hand.

But the hardest test on Episode 1 was piloting the helicopter. For many of us it was the first time we had ever been in a helicopter, the first time we were piloting an aircraft and they wanted us to hover six feet off the ground!

If you haven't seen it yet, check out Episode 1 of ASTRONAUTS: Do You Have What It Takes?

Episode 2 will be broadcast on Sunday 27th August at 9pm.

ASTRONAUTS: DO YOU HAVE WHAT IT TAKES?

I must admit, as soon as I hear that word, ‘astronaut’, my ears prick up and I’m searching around for whoever said it. I’ve always wanted to be an astronaut and I’m in awe of those that have managed to leave the confines of our atmosphere and unshackled from the bonds of gravity float freely outside of this world.

So when I saw an advert from the BBC requesting participants to go through a psuedo-astronaut training and selection programme run by Chris Hadfield, a 20 year veteran of NASA, I jumped at the opportunity. It could be the closest I ever get to experience being an astronaut and here's why...

Quite literary and within the margins of error everyone that has attempted to be an astronaut fails. Not only do you have to be in top notch physical shape (in ways that you will have no idea about), but also must have developed over the preceding decade(s) skill sets that are at the forefront of your chosen field and be ones that are of core requirement for the astronaut corp (which may change!). That requires a lifetime of dedication, hard work and belief. And then, you have to hope that there will be a selection process during those years when you are at your prime!

The last ESA selection process was in 2007-8. During that selection process nearly 10,000 highly skilled applicants from across Europe vied for six places. The odds were pretty slim of making it into the final six and many exceptional candidates didn't. It is the hardest selection process that exists.

But imagine achieving that dream. It would be the ultimate adventure: Imagine seeing the Earth, the most incredible place in the known universe, from the vantage point of orbit. Just that thought leaves me breathless. And so, it’s always been a question I’ve asked myself, do I have what it takes to be an astronaut? Of course, I think I do, but do the experts? What actually do you have to have to be an astronaut?

Fortunately I have had the opportunity to find out. Filming this BBC series putting us through a similar selection process to a real astronaut selection process has been one of the most intense periods of my life. The other candidates are amazing. The stress you see is real and Chris Hadfield and his team made sure it was as realistic as possible.

Episode 1 of ‘Astronauts: Do You Have What It Takes?’ airs BBC 2 at 9pm on Sunday 20th August.

Key Note Lecture at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology

On the 13th January I gave a key note lecture to an audience of over 700 students and faculty at the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology in Saudi Arabia on climate change. Some of whom are leading figures in climate science.

This topic is so important that I'm making the transcript of my talk available for all to read.

The Importance of being On Course

With the sun high in the sky and visibility for miles it would be easy to become complacent with knowing exactly where you are.

But out on Dartmoor with few large features to home in on and a more temperamental weather system than a teenager’s mood, such complacency could be disastrous.

These pictures were taken 12 hours apart. Our campsite views were obliterated by the mist. It came down over the night and lasted the entire following day without relent.

Visibility reduced to mere metres, every direction looking the same. The difference then between an awesome bank holiday weekend in the hills and what could've been an epic battle for survival was knowing exactly where we made camp and just some quite basic compass skills.

We had the former, an awesome weekend away.

It’s all about the (H)Air

Now that summer’s coming round with a scorching hot Spring all of my ‘warm’ jackets are being put away, to the back of the wardrobe not to be looked at again for six months. A question came to mind: What makes a warm jacket? Why is it warm?

I know the answer to this question, having thought about a lot over the years, but I was curious as to whether other people did. Even asking my engineer friends, who pride themselves in knowing how things work, what actually made a jacket warm it did stump them for a few seconds presenting me with a look of bemusement as their minds churned away.

Clothing, be it big, warm jackets in the winter to just a light covering in the summer, is absolutely crucial for our survival. Think about if clothing was never invented, ignoring the fact that we wouldn’t ever have made it out of Africa and assuming we were all comfortable seeing each other in the nude. Popping out even on a summer’s day in the buff sends shivers down my spine just thinking about it and imagine going to a British beach without a wind jacket...brrrr!!

Isn’t it bizarre that despite how crucial clothing is for our survival, for our success in inhabiting large portions of the world, that we rarely give it a second thought about why these materials keep us warm? About why certain materials work better than others? We just know it.

So why do I know about this topic? Because I have gotten cold, very cold! In 2008, during our first attempt to cross the Penny Ice Cap on Canada’s Baffin Island in early spring conditions my feet became so cold they turned blue and were completely numb. It was apparent that to continue on the expedition was to seriously risk my feet or worse and so with no real choice at hand we had to back off the expedition. It was a massive blow back then, an expedition a year in the planning, ruined.

The most curious thing though, was that my team mate, Antony, and I were wearing almost identical clothing. Everything down to our boots was the same and brand new. Antony’s feet were fine. “Warm and toasty” he said. I had no idea why my feet got cold.

Three years later I figured it out. It was the simple fact of my boots being too small. It’s amazing how the best laid plans went awry due to just the simplest of errors. We went back attempting the crossing again in 2011. This time, despite the same brand and model of boots, I wore a size bigger. My feet were fine, more than fine, they were as happy as Larry.

‘Ah, yes of course’ we say to ourselves. ‘Can’t have boots that are too small.’ But why? What is the science behind this? The answer is all around us. Air.

Air is the best* abundant source of insulating material. It’s also free, something nature has found out long ago. Our hair, an animal’s fur and bird’s feathers primary purpose is to trap air. By trapping a good layer of air between your warm body and the cold harsh world, the smaller the heat transfer, the warmer you will be.

The polar bear has even gone one step further; each of their hair is actually hollow allowing air to be trapped within each strand as well as between the individual hairs improving the insulating properties. On top of hollow hairs, the sea otter, with no blubber to keep it warm, relies on the densest fur in the animal kingdom allowing air to be trapped within its fur whilst spending prolonged periods in the water. It’s all about trapping air.

That’s why when there is a wind blowing at you; through your hair, or you’ve dunked your head in a bucket of water**, destroying that trapped layer of insulating air; you lose a lot of heat.

That is exactly how our warm jackets work, be it stuffed with goose feathers or high-tech synthetic fibres. The design of the feathers is optimum to trap as much air in the lightest and smallest structure. Cover these wonderful feathers/fibres in a windproof or even waterproof shell and you’ve got yourself a jacket to rival nature’s best inventions.

So what happened when my boots were too small? My toes pressed up against the front of the boot, squashed the fluffy fibres of my socks and destroyed the trapped air that would otherwise have provided a heat barrier. Instead what I was left with was a direct and solid conduction path to the -35C exterior sucking away my heat. They had no hope.

Next: How do wetsuits keep you warm?

* - the best actually would be a vacuum such as that you find in your Thermos flask but those are pretty difficult and expensive to create and not very practical to be wearing.

** - water in your hair also creates greater heat transfer by evaporation, but that's something for another day...

Baffin Island 2011 - The Polar Bear Story

A re-edit of my 2011 short film documenting what should've been a straightforward journey to the start point of our Arctic expedition. What actually happened blew us away.

A short film showing the start of our Penny Ice Cap crossing in Spring 2011. To get out to our start point we travel by snow mobile over sea ice for about eight hours. During which we came across some local wildlife...

BAFFIN ISLAND 2011 - SETTING UP CAMP

How to setup home on a remote glacier, a re-edit.

After a full days skiing, our bodies are getting tired. The sun is beginning to set and the temperature will soon plummet. Setting up camp requires everyone to work efficiently and quickly.

A New Year's Stomp in the Brecon Beacons

Happy New Year from the Brecon Beacons. Enjoy this little video of our first few days of the year!

The Brecon Beacons national park in Wales is one of the UK's foremost national parks. This New Year's we celebrated the calendar reset in these magical hills. This video was filmed only on an iphone.

Ski Touring in the Indian Himalayas

During my six month travels through India I saw and experienced many things. I was heading into the Himalayas to partake in a 10 day silent meditation course but as soon as I saw the mountains I yearned to be on them. Check out my little stint on a pair of skis in my newest short video:

Two stories about the meditation that happened soon after:

After the Vipassana and The Darkness of the Mind. Find them in the stories section.

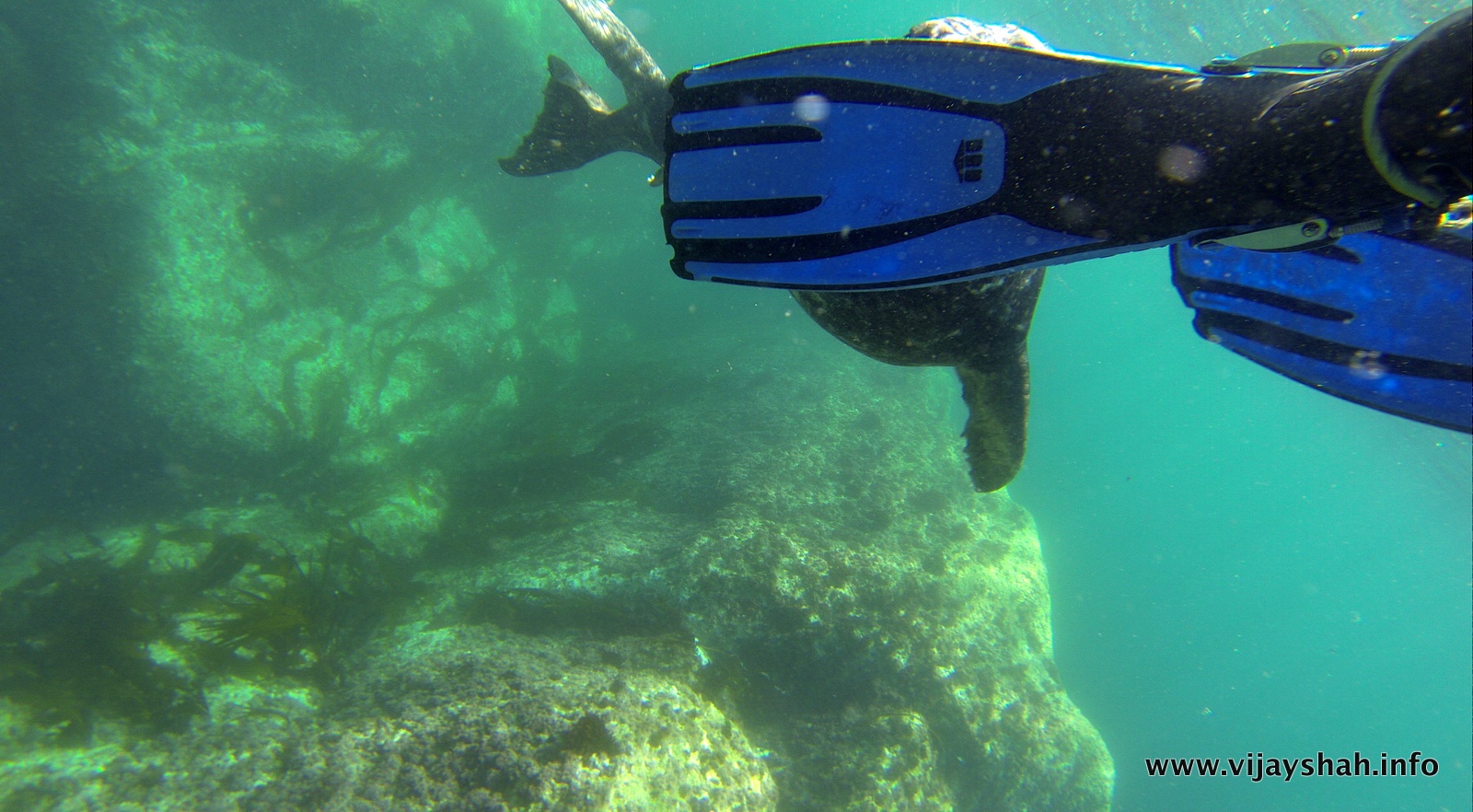

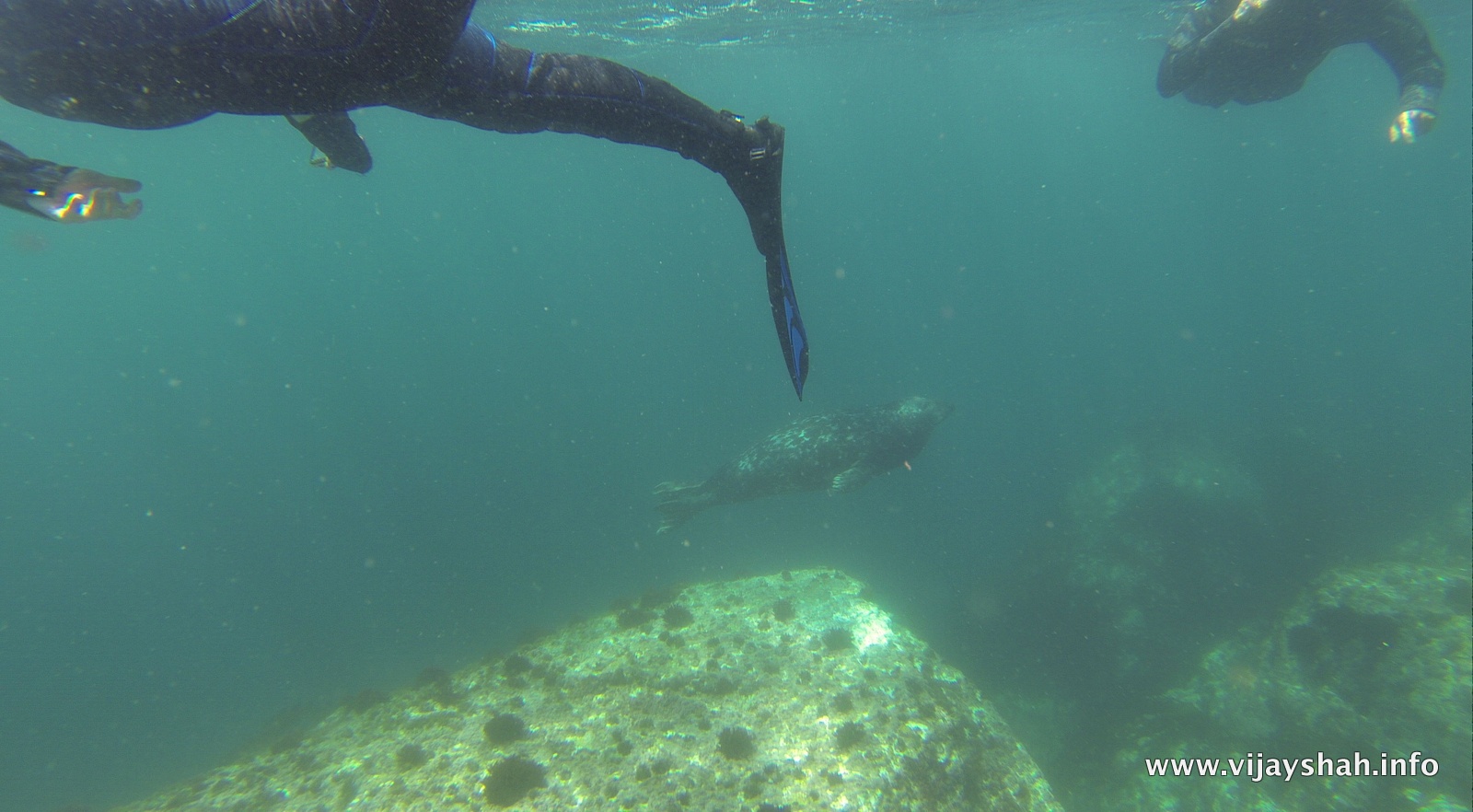

Swimming with seals

What a fantastic couple of weeks of weather we've had. It reminds me of the time I was a child and the summer's were (a little more) predictable. We used to have weeks and almost months of pleasant temperatures and when the conditions are just right there is no where else I'd rather be than in the English countryside.

We came to Cornwall on the summer's solstice to swim with Basking Sharks. Unfortunately we didn't see any but took the next best thing, SEALS!

They are inquisitive and cute, nipping at our fins as they glide past us. The young ones stare at us with big brown eyes, twitching their whiskers before sticking their heads out of the water to check us out more thoroughly.

On our way back we came across a pod of Reese's dolphins, jumping and slapping their tail right in front of our boat. One dolphin was played around with a giant jellyfish pushing him out of the water and back down again. But no photos of these (camera malfunction).

New Showreel for 2014

Just finished my new showreel for 2014. Check it out: