Senja, Arctic Norway - Cheap Accessible Adventure

Scandinavia is so accessible to us in the UK with and with the ‘last wilderness’ in Europe it really is a must for anyone loving the outdoors. Arctic Norway is even more accessible than most of Scandinavia through the gateway town with international airport Tromso. I’ve flown through Tromso before, heading over to the high Arctic islands of Svalbard but on this occasion I was keen to see what was there to do with only one or two weeks to spare.

That’s where we discovered the island of Senja and spent six days traversing the island, hardly seeing a soul. So if you’re competent in wild camping, love hiking and can read maps in low vis. (and like that sort of thing) then this is really awesome trip. Plus, it’s a super cheap trip if you play it right.

From Tromso, you can take a ferry, that takes only a couple of hours, that drops you to the tiny little crossroads of Silsands and from there you’re on your own. Heading straight up into the hills of the interior you have the entire island to yourself.

Water can be scarce in the high interior where there aren’t many rivers and if you’re lucky enough to have fabulous weather, like we did, then that means that the small streams that exist will be very low. So make sure you have plenty of water containers to fill up when you do find a water source and enough fuel to boil away water taken from less than perfect sources.

Hiking across the interior takes you over a mountain pass. Despite it only being around 1,000m high, being this far north means that you will have to pass over snow slopes and it can get bitterly cold with the weather exposure even in mid-August.

Despite not seeing another person, we did see plenty of reindeer. Having spent a fair bit of time in Scandinavia I know how common reindeer are and that they don’t really fear humans at all. Many a times I’ve woken up in my tent to the sounds of a herd of reindeer walking straight through our camp. As well as not being scared by humans they are also not bothered or interested in us. But that was different on Senja, clearly not seeing humans that often they were enthralled by our presence and kept on hiding behind the next rise to see us before running off to try and sneak up a different way to get a view. We were completely bemused and we enjoyed turning around every few minutes to find a couple of reindeer following us. They will stop in their tracks, frozen like a children’s game and start again when we turned back around.

Depending how quick you go, you’re looking at 4-8 days to get to the southern side of the island where a ferry leaves fairly frequently. Be sure to check out the days and times and make sure you’re there on time. You cannot bet on the weather but you can bet on the ferry times.

At a push, if you’re well organised, you could do this on a week’s trip, ideal for those of us with limited holiday. We took two weeks out and spent the second week exploring Tromso and other parts of the Arctic.

If this does inspire you to get to Senja send me over a photo. Happy planning!

SNAPSHOTS

ASTRONAUTS: WHY THE FUTURE MUST HAVE WINGS

**SPOILER ALERT** If you haven’t seen it yet, watch Astronauts: Do You Have What It Takes? Episode 4 on iPlayer first.

One of the tests that we were given was to present to the panel on a topic of space exploration. Being an aerospace engineer my talk was on a topic that has fascinated me since childhood: Access into Space.

Why The Future Must Have Wings

The hardest part of space travel in our near solar system is getting into space in the first place; out of our atmosphere.

So far the only way we have reached orbital spaceflight is by rockets and these, on the whole, are inefficient, expensive and unreliable.

In comparison, aircraft are very efficient, reusable and for anyone who has flown half way across the world on holiday, incredibly affordable.

In order to understand the difference between these two technologies that have developed over a similar timeframe we really need to understand how a rocket engine works:

· A rocket engine operates under the same principle of if release a blown up balloon. By accelerating a large amount of gas out of the back, an equal and opposite force is imparted onto the rocket pushing it upwards, as described by Newton’s third law of motion.

· The rocket is generating these hot, compressed gases internally through combustion. For any combustion be it a rocket or a campfire, you need three things: a fuel source, an oxygen source and a heat source. The rocket carries all of these components on board with it in stored energy and as a result becomes extremely heavy. This is evident when we see that the oxidiser is six times heavier than the fuel source!

· But this does give it one big advantage, the rocket can operate in the vacuum of space but must result in expending it’s stages as it goes up to reduce mass. And the atmosphere is just a hindrance.

In comparison, the airliner doesn’t see the atmosphere as a disadvantage but uses it beneficially in three different ways:

1. The atmosphere provides the aerodynamic lift on the wings providing the upwards force opposing gravity.

2. Instead of carrying the oxygen with it, the jet engine uses the oxygen in our atmosphere for combustion, and

3. Crucially the jet engines use the air as the working fluid or propellant. The big fans and compressors, suck the air in, compress it, heat it up in the combustion chamber and accelerate it out the back creating the equal and opposite force pushing the aircraft forward.

A much more elegant and efficient solution. Clearly the future of space access must our atmosphere as a benefit rather than always seeing it as a hindrance.

That’s why there is a lot of interest in developing single-stage-to-orbit spaceplanes.

A spaceplane takes off and lands just like an aircraft and uses an air-breathing engine and wings to climb to the upper reaches of our atmosphere travelling at Mach 5, or five times the speed of sound. As the air becomes too thin for the air-breathing engine, the intakes close off and it switches to a rocket engine, accelerating to Mach 25, for the last and final push into orbit.

Now imagine this, as our single stage to orbit vehicle hasn’t jettisoned it’s fuel tanks on its way to orbit, as soon as we reach orbit we have many more options open to us: We can refuel the spaceplane with a conveniently placed orbital refuelling station giving it enough fuel to gently pop over to the moon for a supply trip or a tourism visit and after a few days it will coast back to Earth and re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere. But the benefits don't just stop there, with the much superior re-entry characteristics the spaceplane offers it can land on one of several runways around the world and after a quick check over, a refuel, it is ready to go again. Completely reusable.

And that is why the future must have wings.

Astronauts: Do You Have What It Takes? Episode 5 is on Sunday 24th September at 8pm BBC2.

ETHIOPIA: Episode 8 - In Search of Wildlife

For the last part of our journey we headed to southern Ethiopia famed, at least in Ethiopia, for it's wildlife. What we found though was the immense pressure that livestock agriculture was having on the environment.

But that didn't stop us from having the most unique safari experience ever. Join us for the eighth and last film of our journey around Ethiopia. Episode 8 - In Search of Wildlife

ETHIOPIA: Episode 7 - Of Music And Angels

Lalibela, Ethiopia's Jerusalem, a town of faith unchanged for over a thousand years. Episode 7 takes us into the realms of the rock hewn churches, carved out by the angels and at the centre of Ethiopia's Christian faith. But first of all we start with stumbling into a music video at the honey market...

ETHIOPIA: Episode 6 - Salt

In the hottest place on Earth the Afar people toil throughout the scorching day to harvest thousands of kilograms of 'White Gold'.

The Afar have evolved specially to be able to withstand and work in this hot, arid landscape with little or no water.

ETHIOPIA: Episode 4 - Erta Ale

Ever found yourself on the edge of an active volcano? We did in the far North Eastern corner of Ethiopia. Join us for episode 4 of our travels around the fascinating country that is Ethiopia. This is my scariest adventure to date and the most incredible thing I have ever seen! Episode 4 - Erta Ale

ETHIOPIA: Episode 3 - Buna

Ever had coffee roasted on an open fire, grounded and served right in front of you? We did, in a small village 3,000m up in the Simien mountains. Captured beautifully in our latest film.

Check out Episode 3 of our adventure around Ethiopia: Buna

SNAPSHOTS: HIMACHAL PRADESH

As part of the snapshot collection, here is the state of Himachal Pradesh in the Indian Himalayas.

Check out the other snapshot collection videos...

Blonde, Blonde Hair

A Thousand Years of History

A thousand years ago, King Lalibela of Ethiopia, helped by angels carved twelve magnificent churches out of the ground beneath his feet in a single night. He dug down into the ground and from solid rock carved each church before hollowing out the centre. That is how the legend goes, which our guide vehemently believed. And despite their architectural wonder it is the belief of these churches, belief of Christianity amongst the Ethiopians that brings these buildings, some of the oldest in Africa, alive.

SNAPSHOTS: GUJARAT

The Most Incredible Thing I Have Even Seen

Dancers on the Sand

**TWO NEW FILMS**

Really excited to have two new super short films for you to see. Quite different from the recent films, these two shorts are based on the tropical paradise that is the Andaman Islands.

SNAPSHOTS: ANDAMAN ISLANDS (03:36)

DANCERS ON THE SAND (02:27)

As the sun sets on the secluded beaches of the Andaman Islands, a bizarre creature searches for a home.

The Azores: Islands of Adventure

Peaking out of the vastness of the Atlantic ocean lie the volcanic islands of the Azores. Equidistant between Europe and North America they are neither from the old world or the new but instead a world of their own. This summer, before which I never knew these islands existed, I was fortunate to spend a couple of weeks visiting. They're incredible!

SHOWREEL 2015: VIJAY SHAH

Updated showreel for 2015. Check it out! :-)

Ashamed

A feeling of shame came over me last weekend. I was sitting in a canoe gently paddling down a river listening to an amazing chorus given off by a multitude of birds. I wasn’t in the wilds of the Amazon, Africa or even Scandinavia. I was here in the UK. A mere one and a half hours from Bristol, on the English and Welsh border I experienced something quite spectacular.

Red kites soared overhead descending close, right over our heads. Swifts darted between and around us, pulling the most impressive of aerobatic turns to prey on flying insects. Song thrushes perched on the bowed ends of reeds sang their sweet melody. A cuckoo interrupted and a woodpecker punctuated. Mallard ducks swam by the river banks watching closely at their brood of fluffy ducklings as they played amongst the fallen branches and the goosanders showed off their hairstyles.

This was all captured in one scene, a picture perfect postcard of Britain. Further along we canoed through a gang of swans, adolescent cygnets from the last season still sporting some grey. As we slowly paddled through they silently parted either side in the most poetic of dances. Another group in the distance took off, silhouettes, mere metres over our heads, whilst a mother curled her long body up over her precious eggs on the banks.

My shame came from my surprise to this feeling of amazement at having found this spring time paradise in our country. I attribute wilderness and wildlife to other places, not to industrialised Britain that I have accepted as tamed and boring. And I feel bitterly ashamed by this unconscious view I held. I feel embarrassed that with this view I am letting down all those people that have been trying to re-wild Britain, those that possess the imagination of what Britain can be and once was and with the faith to tirelessly campaign towards this goal.

So here’s to those activists, lobbyists, environmentalists that have taken up this baton. Here is to those giving a voice to the real natives of this fair land and to their successes allowing me to experience this beautiful nature, right on my doorstep.

The job though isn’t done and we didn’t see any otters. The next time I am canoeing down the Wye I am hopeful that I shall.

Warm-In' Water

Every diver knows that small apprehensive feeling as they shuffle forward on their large penguin feet, rocking like a pendulum on the moving deck. Top heavy with hoses and tanks hanging off them they muddle towards the free edge, ready to step forward into the deep blue ocean. Having cleared that hazardous journey, albeit mere metres, they balance themselves precariously on the threshold.

The last checks are performed; regulator entered into mouth, buoyancy aid inflated. Matching time with the surging deck, with one hand covering the face mask and mouth piece whilst the other holding the ancillary hoses, they step forward into the abyss. Clearing the boat they enter into the ocean, the senses are momentarily overwhelmed by the strange new world: Bubbling water cloud their vision and the splashes distorts all sound. But it’s the thrill of cold water felt throughout the body as the blue swallows them all that gives the greatest shock. The tight wetsuit flushes with cold, ocean water, giving the diver a decisive shiver.

The last place I experienced this was in the Andaman Islands, a beautiful set of islands in the tropical waters of the Indian Ocean. The waters though are warm, far warmer than when the legendary diver Jacques Cousteau explored these waters and told the world of the untouched treasures beneath. Sadly, as a result of the warm waters many of the shallow coral reefs have died and are a barren landscape of beige, calcium carbonate skeletons, a mere suggestion of what once was.

Diving here thus means going deeper, to 35 metres, where marine life can still thrive, albeit with the reduced sunlight of the deep. To dive deeper poses many challenges to the diver including nitrogen narcosis, decompression problems and a reduction in air supply. But it also means that you have to be more aware of your body temperature – a cold diver can quickly become a seriously ill diver and it gets a lot colder below. More than once I saw divers signal to their buddies with the international ‘I’m cold’ signs of folded arms rubbing each other preceding a flurry of hand communication and finally their ascent to the surface and the warmer waters above.

Maybe their bodies could not cope with the cold or maybe their wetsuits weren’t thick enough, at any rate they were not insulated enough. In my last post I had flamboyantly broadcasted how keeping warm is really about trapping air, but as the name suggests, wet suits are used in the water and there isn’t much air there. So how do they work?

Firstly, air doesn’t have any super special properties but the three things that make it the ideal insulator are that it is abundant, free and is a gas.

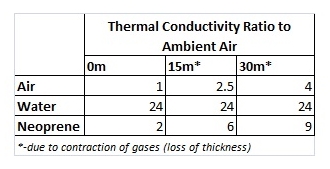

The magic of the wetsuit lies within the neoprene. Neoprene is a plastic foam material that is impregnated with small bubbles of nitrogen gas (like an Aero chocolate bar). Pure nitrogen is slightly better than air at thermal isolation. Putting all this in context, whilst water loses heat an incredible 25 times faster than air, neoprene, due to the amount of air bubbles trapped within it, loses heat at only nine times as fast at 30m depth (only twice as fast on the water surface).

The ingress of water into the suit, which gives that initial uncomfortable shock that all divers experience, is unfortunately a necessary evil. An absolutely skin tight neoprene suit that has no air gaps would be impossible to get on and off (think how thin tights are) and to keep the seals watertight requires some flashy suits that makes for very expensive bits of clothing.

However, we do that too. They’re aptly called dry suits and divers going for extended periods of time underwater or ice diving frequently uses this type of suit to stay warm. Despite being an avid diver and a frequent visitor to the Arctic I have yet combined the two... and I’m aching to try!

Coming back to the point on wetsuits, they rely on trapping a small amount of water between the skin and the neoprene material, keeping that same water there throughout the use.

By trapping only a thin layer of water which is very quickly heated up to body temperature the amount of heat lost would reduce dramatically. In contrast if the trapped water was constantly changing, such as in a loose wetsuit, the body would expend a lot more energy heating up the newly trapped water each time. By transporting the same heated up water with them divers achieve the goal of using the water too as insulation – albeit much less effective as the neoprene covering.

For anyone who has dived, surfed and swam both with and without wetsuits they would quickly attest to how much warmer it is with one.

The wetsuit is an incredible invention that allows us, without ever thinking about it, to dive deep in the Andaman Sea. Half an hour into my last dive on the Andaman Islands when many of the group had already ascended due to cold or low air I came across one of the most majestic and curious of ocean creatures. Magical!

Next: How to stay cool.

If you’re like me and need some equations, see below you science fiends:

There are three types of heat transfer; conduction, convection and radiation. The one that we are talking about most of the time is conduction.

Conduction is a nice long word that basically describes how heat (energy) is transferred between neighbouring molecules, or objects touching each other. The simplest form of understanding this is that if one has more neighbours that are very close together there would be more heat passed (lost). If there isn’t that many neighbours and they are all far apart then there would less heat energy passed on. A solid material has lots of neighbouring molecules all very close together whilst a gas has the exact opposite, with liquids sitting somewhere between.

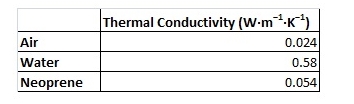

This property of the material is known as the thermal conductivity.

The other factors that affect heat transfer is described in the conduction equation below.

Heat conduction (per unit time) = (Thermal conductivity) x (Area) x (Temperature difference)/Thickness

It all describes what we all know from common sense. If your jacket (insulation) is thick then you lose less heat, but if you have a larger surface area exposed then you will lose more heat. The final part of the equation suggests that if the difference between temperatures is greater, then more heat is lost, hardly surprising really.

The differences in thermal conductivity are:

Diving deep under water increases the pressure which would lead to the compression of gases, the values for thermal conductivity are given below:

It’s all about the (H)Air

Now that summer’s coming round with a scorching hot Spring all of my ‘warm’ jackets are being put away, to the back of the wardrobe not to be looked at again for six months. A question came to mind: What makes a warm jacket? Why is it warm?

I know the answer to this question, having thought about a lot over the years, but I was curious as to whether other people did. Even asking my engineer friends, who pride themselves in knowing how things work, what actually made a jacket warm it did stump them for a few seconds presenting me with a look of bemusement as their minds churned away.

Clothing, be it big, warm jackets in the winter to just a light covering in the summer, is absolutely crucial for our survival. Think about if clothing was never invented, ignoring the fact that we wouldn’t ever have made it out of Africa and assuming we were all comfortable seeing each other in the nude. Popping out even on a summer’s day in the buff sends shivers down my spine just thinking about it and imagine going to a British beach without a wind jacket...brrrr!!

Isn’t it bizarre that despite how crucial clothing is for our survival, for our success in inhabiting large portions of the world, that we rarely give it a second thought about why these materials keep us warm? About why certain materials work better than others? We just know it.

So why do I know about this topic? Because I have gotten cold, very cold! In 2008, during our first attempt to cross the Penny Ice Cap on Canada’s Baffin Island in early spring conditions my feet became so cold they turned blue and were completely numb. It was apparent that to continue on the expedition was to seriously risk my feet or worse and so with no real choice at hand we had to back off the expedition. It was a massive blow back then, an expedition a year in the planning, ruined.

The most curious thing though, was that my team mate, Antony, and I were wearing almost identical clothing. Everything down to our boots was the same and brand new. Antony’s feet were fine. “Warm and toasty” he said. I had no idea why my feet got cold.

Three years later I figured it out. It was the simple fact of my boots being too small. It’s amazing how the best laid plans went awry due to just the simplest of errors. We went back attempting the crossing again in 2011. This time, despite the same brand and model of boots, I wore a size bigger. My feet were fine, more than fine, they were as happy as Larry.

‘Ah, yes of course’ we say to ourselves. ‘Can’t have boots that are too small.’ But why? What is the science behind this? The answer is all around us. Air.

Air is the best* abundant source of insulating material. It’s also free, something nature has found out long ago. Our hair, an animal’s fur and bird’s feathers primary purpose is to trap air. By trapping a good layer of air between your warm body and the cold harsh world, the smaller the heat transfer, the warmer you will be.

The polar bear has even gone one step further; each of their hair is actually hollow allowing air to be trapped within each strand as well as between the individual hairs improving the insulating properties. On top of hollow hairs, the sea otter, with no blubber to keep it warm, relies on the densest fur in the animal kingdom allowing air to be trapped within its fur whilst spending prolonged periods in the water. It’s all about trapping air.

That’s why when there is a wind blowing at you; through your hair, or you’ve dunked your head in a bucket of water**, destroying that trapped layer of insulating air; you lose a lot of heat.

That is exactly how our warm jackets work, be it stuffed with goose feathers or high-tech synthetic fibres. The design of the feathers is optimum to trap as much air in the lightest and smallest structure. Cover these wonderful feathers/fibres in a windproof or even waterproof shell and you’ve got yourself a jacket to rival nature’s best inventions.

So what happened when my boots were too small? My toes pressed up against the front of the boot, squashed the fluffy fibres of my socks and destroyed the trapped air that would otherwise have provided a heat barrier. Instead what I was left with was a direct and solid conduction path to the -35C exterior sucking away my heat. They had no hope.

Next: How do wetsuits keep you warm?

* - the best actually would be a vacuum such as that you find in your Thermos flask but those are pretty difficult and expensive to create and not very practical to be wearing.

** - water in your hair also creates greater heat transfer by evaporation, but that's something for another day...